The main hub of the game, also known as the Waiting Room, features a weapons vendor and a woman who sells you decals, which are basically character buffs. The weapons vendor is an unassuming man sporting a bowl haircut and a Hitler-esque mustache, while the decal woman pole dances on a small stage, as pots of gross-looking gumbo swirl around her on a conveyor belt. When you want to level up, you walk over to a mechanical head and watch as it plunges a series of wires into your body, making tweaks and adjustments that will surely help you on your climb to the top of the Tower of Barbs. There’s a Grim Reaper-like character who wears colorful shades, moves around on a skateboard, and calls you “senpai.”

This is a Suda51 game, alright.

Let It Die’s premise is simple enough to grasp. You pick a human body from a moving train, and you’ll try to train that fighter up and get him or her up as high as you can in the apocalyptic Tower. If you die, you lose all of your gear and level progression, and you pick a new fighter. If you’re willing to shell out some IRL cash, or you’ve had some in-game currency saved up, you can revive that fighter and live to see another day. As much as I’d like to chastise Let It Die for beating players over the head with the in-game insurance policy and its multitude of other microtransactions, after spending a few days with the game, I’ve found that the F2P model really doesn’t hurt the gameplay all that much, if you choose not to let it.

Early on in the game, you’ll find yourself strapped for cash. And when you do inevitably die in a battle against an over-leveled Hater (NPC versions of player fighters who died on the level you’re on), it might be tempting to spend some real money to keep playing. But that isn’t the point of Let It Die. In fact, once you acknowledge that these microtransactions are there not to help you win, but to get you up the Tower faster with fewer breaks, it becomes much easier to slow down and take on the game at your own pace. Your fighter died? No big deal. Just start over with a fresh one, and buy the fighter back from the freezer once you’ve accumulated enough in-game coins.

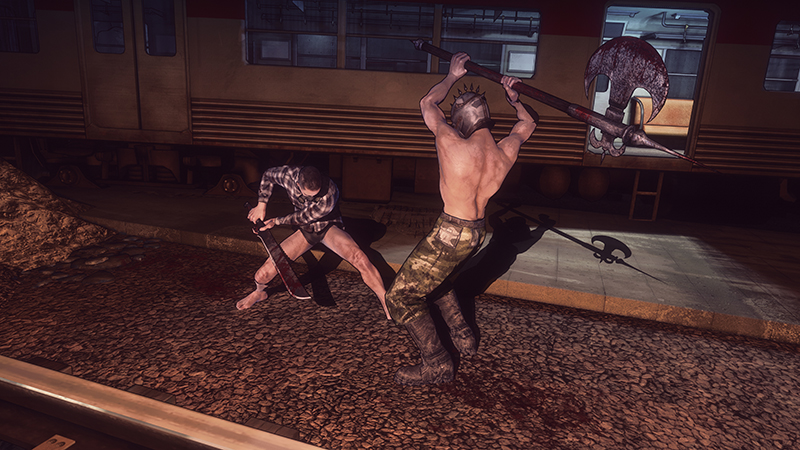

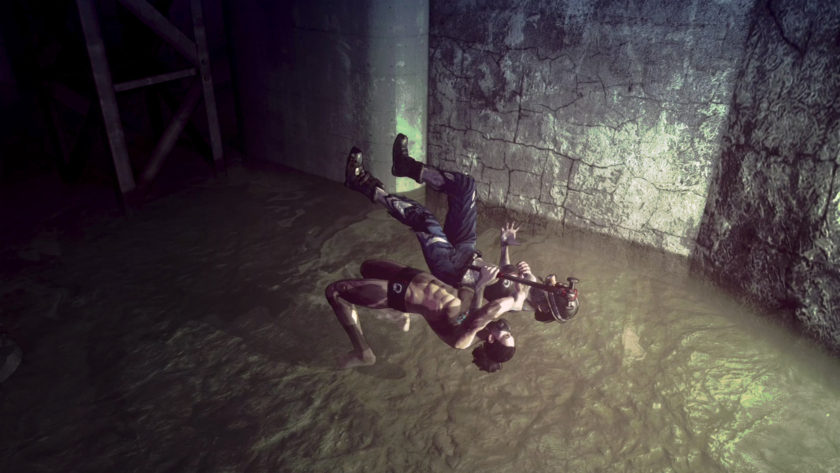

Where the game falls short in level design and variety in mob enemy patterns, it makes up for with the fun action combat and the personality just oozing from all the bosses and NPCs you can interact with. The dungeon crawls in between bosses can feel like a slog because of its linearity and drab design, but Let It Die keeps you hooked with the range of weapons available in the game. Let It Die adopts a weapon equipment system similar to the one we see in From Software’s Soulsborne games. Your fighter can equip weapons in their left and right hands, and you switch between them with the d-pad buttons. Stamina management plays a huge part in the fights, you can dodge enemy attacks, or you can hit a block button at the right time to deliver a counterattack. As your mastery level with specific weapons increases, you unlock weapon moves and patterns, lending the game some much-needed attack variety we never really get to see in the first ten levels. It’s just unfortunate that the regular mob foes never seem to learn any new moves beyond the regular R2 attacks.

While the fighter’s movements didn’t feel quite as fluid or responsive as I’d have liked, it’s easy to appreciate the depth and complexity in Let It Die’s combat. You won’t make your way to the top of the Tower simply by button-mashing and playing it like a hack-and-slash game; you have to time your attacks and dodges, and enemies will punish you if you don’t manage your stamina properly.

When you’re low on health, you look for rats and and frogs on the ground. You can stomp on them, or eat them alive. The choice is yours, but be warned that handling these animals one way or another will have different effects on your character and the enemies. If you’re feeling a little overwhelmed by all of the gory violence going on in the dungeons, take an elevator back to the Waiting Room, where you’ll be greeted by the wacky NPCs who simply don’t give a shit if you think they’re weird or not.

As you climb higher and higher, you will, of course, encounter boss fights. Thankfully, these aren’t just powered up variations of regular enemies you’ve already fought on previous levels. The monstrosities are all grotesque in design, and they have specific mechanics you’ll need to master if you’re to have a chance in hell of taking them down. One early game boss, for instance, was a lumbering hulk who could probably kill my fighter in two hits. However, it was also blind, and it reacted to any sound my character made. You’d then have to try to exploit its blindness by luring it to one side of the arena, and then circling around to avoid its attacks and strike from behind. The bosses were the centerpieces of the Tower of Barbs, and they’re a delight to fight against.

If there’s one complaint to be had with the game’s PVE aspect, it’s that the game’s menus and interface are an unorganized mess. Closing your inventory menus requires you to hit the circle button to back out, but closing your lore handbook requires you to press square instead. The character screen is cluttered, and it’s often hard to find what you’re looking for. Using items in your inventory requires you to flick the touchpad, and I suspect this is meant to be a convenient shortcut for players. But oftentimes you’ll have to check your items in the menus anyway because certain item icons can look similar to each other, and it’ll take you a few hours to get accustomed to each one. Fonts are also needlessly small, and cannot be adjusted, which is a nuisance. Thankfully, you can largely get by with just the knowledge of how to change your weapons and armor. As you spend more time with the game, you do eventually learn how to sift through all the junk in your ugly menus. It’s just a shame that getting comfortable with the UI requires such a significant time investment.

Despite the drab-looking environments and bland, linear corridors that you’ll be treated to most of the time, Akira Yamaoka’s (known for Silent Hill and Shadows of the Damned’s music) work on the game’s score is top notch, as expected of the video game music legend. It likely won’t be for everyone, but the intense guitar riffs, featuring music from over a hundred Japanese rock artistes, fit the game’s atmosphere perfectly. The music and sound direction here is commendable, to say the least.

While the PVE side of Let It Die is solid enough, PVP does seem a tad unbalanced at the moment. As mentioned previously, if you die in a dungeon, you’ll lose your fighter. That fighter will be brought back to life as a Hater who wanders around the level they died on. This means that other players can encounter your Hater if they’re on the same level, and so can you. While this didn’t happen too often during my experience with the game, it is possible to encounter level 30 Haters even on the second and third floors of the dungeon, where you’ll likely still be around level one to five. A Hater’s move set isn’t terribly difficult to predict, but fighting an overleveled one means you’ll be taking a huge risk, and you’ll probably end up wasting a lot of resources just from taking down that one enemy. Considering that your own Haters can be sent out to hunt down other fighters for items and treasures, this seems like a mechanic that can be easily exploited.

Not to mention, other players can invade your base and fight you. If they emerge victorious, your fighter will be forced to clean the enemy player’s bathroom (ha), and that fighter will be unavailable to you until you’ve defeated that player and take back what’s yours. With a roguelike game like this one, losing gear and progression to tough dungeon bosses is just par for the course. However, losing all of your progression to exploitable PVP mechanics and other elements that you have no control over is going a little overboard. Considering that Let It Die is an always-online title, this means that players will always run the risk of having all their stuff taken from them because of another player’s actions.

You could always fork out some real money to get your character back, of course, but no one likes being forced to do that. I’m not a fan of this concept, and Let It Die could do with a single-player mode, with the PVP stuff relegated to a separate mode for those who want it. Or at the very least, the consequences could be a little less severe.

That being said, Let It Die feels pretty damn polished for a game that costs nothing to play. In spite of the terrible menus and potentially broken PVP aspects, Let It Die is still very much a fun roguelike action RPG you can easily sink hours into. It’s got all the odd charm and personality you’d expect from a quirky – and that’s putting it mildly – Suda51 game, and even if you’re not a fan of the gameplay, you’ll at least have a few hours of fun with these crazy personalities. Given that the barrier to entry is literally non-existent, save for the possibility of a PS4 with no storage space, I’d highly recommend this one to fans of the genre.

There are no comments.